Editor’s note: This report is based on public and private documents and data, as well as interviews with almost two dozen people, including current and former government environmental officials, economists, biologists, indigenous people, academics, technicians and researchers who have witnessed the deforestation in the Eastern region of Paraguay and the reasons it has occurred.

By Aldo Benítez

Correspondent/Bajo la Lupa

Ten years ago, the Paso Kurusu ranch covered 53,953 acres in the Atlantic Forest and its land was considered one of the largest forest reserves in Paraguay. At the time, the World Wildlife Fund classified the forest as essential to the conservation of stands of old growth trees in the Eastern region of Paraguay, an area of wide plains, valleys and red earth.

In the years since, the forest in Paso Kurusu has been destroyed.

Almost 50,000 acres were stripped of the trees between 2011 and 2020, despite a federal law in effect since 2004 that protects the Atlantic Forest and prohibits the clearing of trees. The owner of this now-barren land is Brazilian businessman Ulises Rodriguez Teixeira.

Since Rodriguez Teixeira settled in Paraguay more than two decades ago, environmental officials say he has become one of the most prolific deforesters in the Eastern region, where Paraguay shares a border with Argentina and Brazil.

The records of Paraguay’s government environmental protection agencies over the last 10 years show that no other property owner in the agroindustrial sector has accumulated so many complaints or been the subject of as many investigations.

In 2017, Rodriguez Teixeira received the largest fine ever imposed by Paraguay’s Ministry of the Environment– $216,700 — for deforestation of 12 properties that he owned between 2011 and 2012. The Minister of Environment at the time, Rolando de Barros Barreto, signed the order. But four years later, Rodriguez Teixeira has not paid the fine. He appealed and the issue remains unresolved by Paraguay’s courts.

“The name of Rodriguez Teixeira is a reference point when talking about deforestation in the Eastern region,” said de Barros Barreto in an interview.

Despite Paraguay’s strict environmental regulations – its Zero Deforestation law has been in effect since 2004 – data from the Global Forest Watch satellite system shows that more than 3 million acres were razed in ten of the 14 states in Paraguay that are part of the Atlantic Forest between 2004 and 2019. In all that time, not a single person was sent to prison for deforestation.

There are not enough environmental officials to enforce deforestation regulations in Paraguay, a country of 7 million people that is roughly the size of California. And there are not enough judges versed in environmental law, which means their decisions are not often rooted in environmental concerns.

Then, too, there are economic pressures. The Atlantic Forest is being cleared by agribusiness companies to make way for lucrative soybean production and livestock that makes Paraguay one of the largest meat exporters in the world.

Soy exports generate slightly more than $3 billion per year, according to the National Sustainable Commodities Platform, making Paraguay one of the world’s largest soy exporters.

Cattle farming in Paraguay generates about $ 1.35 billion per year in meat exports, placing the country among the largest beef producers worldwide. Some 52 percent of the country’s livestock is raised in the Eastern region where the Atlantic Forest is located, according to data from the Paraguayan Board of Sustainable Meat.

The story of deforestation of the Atlantic Forest, lax environmental enforcement and competing economic interests is set in Paraguay. But it has ties to Brazil, which shares the forest with Paraguay, and it resonates throughout Latin America.

“We did nothing to prevent the destruction of the Atlantic Forest,” said Fatima Mereles, former president of the National Council for Science and Technology in Paraguay. “Today, the entire Atlantic Forest is losing its resilience.”

Most of Rodriguez Teixeria’s land is in the Atlantic Forest, a biodiverse region with more than 2,000 species of animals. The forest is home to more than 930 species of birds. There are more than 20,000 species of plants in the Atlantic Forest, 40 percent of which are found nowhere else on Earth.

At least 450 species of trees have been recorded in just 2.5 acres of the Atlantic Forest, more than all the species found on the U.S. Eastern Seaboard.

The Atlantic Forest is second only to the Amazon in ecological and environmental importance in Latin America, according to the World Wildlife Fund. But it is also considered one of the most threatened.

The majestic forest once stretched over more than 500,000 square miles in Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina. In the past 10 years, 85 percent of the original forest has been razed, leaving only 75,000 square miles intact.

Paraguay’s Eastern region is home to the Atlantic Forest, a vital ecosystem of unique plant and animal species second only to the Amazon and one of the richest natural areas on the planet. Foto: Shutterstock

Paraguay has a wealth of ecosystems that biologists and environmental specialists consider unique. Divided into two distinct regions – the Eastern and the Western — each one is part of an important ecoregion in Latin America.

In the Eastern region, the Atlantic Forest covers ten states in Paraguay and at least twenty protected wild areas, including the Mbaracayú Forest Biosphere Reserve, one of two natural biospheres recognized by UNESCO in Paraguay. The other is the Chaco Biosphere Reserve.

In the Western region, the upper part of the Paraguayan Chaco is part of the great Pantanal, the largest wetland in the world, which is shared with Bolivia and Brazil. Some specialists consider it the most biodiverse ecosystem on the planet. It is home to species such as the giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) and the giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus) that are classified in danger of extinction and not found anywhere else in the world.

Then there is the Guaraní aquifer, the third most important subterranean reservoir of fresh water in the world. The aquifer covers parts of Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay. In Paraguay, 10 of the states that are part of the Atlantic Forest are on the aquifer.

Protected wild areas were established in 1994 by the Paraguayan government in response to the high rate of deforestation that was already occurring. The idea, in principle, was to create a system where public-private intervention would ensure conservation.

But 27 years later, deforestation continues.

It is in the environmentally sensitive Eastern region, in the Atlantic Forest, that Rodriguez Teixeira settled and established his soy and livestock operations.

PARAGUAY, COUNTRY OF OPPORTUNITIES

Ulisses Rodrigues Teixeira was in his 30s when he arrived in Paraguay in the late 1990s. He came from the state of Paraná in southern Brazil where he was already an influential businessman. In 1992, he represented the Brazilian government during its 21st Economic Mission to Japan. In Paraná, his family still has investments and companies in the agricultural sector.

He settled between the states of San Pedro and Canindeyú, but he was not the only Brazilian businessman who established roots in the region. In this area of Paraguay close to the border with Brazil, agribusiness has a Portuguese accent. For Teixeira it was like being at home.

Brazilians began arriving in Paraguay in the 1960s, drawn by cheap, arable land in the region that borders Brazil. They cleared trees for large-scale agriculture, an activity that was welcomed by Paraguay’s federal government as a way to convert “unproductive” land into communities that could improve the lives of peasant families. As if to underscore the point, there are photographs from the 1980s and even the 1990s with people posing with huge trunks of native wood, freshly cut and loaded on trucks in the Atlantic Forest.

Paraguay’s soy industry was pioneered by Brazilian growers who helped the country become the sixth largest producer of soy and the fourth largest exporter in the world. Argentina, Brazil and Russia are the largest buyers of Paraguay’s soy exports, which contribute 18 percent to the country’s GDP.

Today, roughly 14 percent of all arable land in Paraguay – more than 1.1 million acres – is in the hands of Brazilian businessmen, according to De Olho nos Ruralistas, a research organization that focuses on agribusiness in Brazil. At the end of 2019, there were 137 Brazilian companies in Paraguay — 32 percent of companies operating with foreign capital, according the Central Bank of Paraguay. The vast majority are dedicated to agriculture.

In the lucrative soy business, Rodriguez Teixeira is one of Paraguay’s biggest players, both as a producer of soy and as a property owner who leases his land for soy production.

Rodriguez Teixeira — who in Paraguay uses the Spanish-language version of his first name with one s (Ulises) and his surname with a z (Rodriguez) at the end – owns at least nine farms and he appears as a board member on at least two other companies linked to agribusiness.

The combined land holdings are more than five times the size of Paraguay’s capital city, Asunción. In just five ranches, Rodriguez Teixeira and his family have 124,872 acres, all located in the Atlantic Forest.

On many of the rural properties, Rodriguez Teixeira’s relatives appear as owners. For example, in INFONA’s records, one of the owners of Paso Kurusu is his daughter Renata Teixeira. His siblings and other relatives also appear as owners of the properties.

Data from Paraguay’s rural land registry show that Rodriguez Teixeira and his family own at least another 25,000 acres in other areas of Paraguay. The extensive land holdings rank Rodriguez Teixeira sixth among Brazilian landowners in Paraguay, according to a report by De Olho nos Ruralistas.

Despite his land holdings and soybean operations, Ulises Rodriguez Teixeira was not known to most Paraguayans. But that changed in October 2009, when the newspaper ABC Color published a bombshell: Rodriguez Teixeira had cut a lucrative deal to sell his Paso Kurusu ranch to the Paraguayan government.

ABC Color, one of the most widely read newspapers in the country, reported that an agreement had been reached between Rodriguez Teixeira and the government of then President Fernando Lugo that established a payment of USD $30 million for the 53,953-acre Paso Kurusu ranch.

The newspaper revealed that Rodriguez Teixeira had purchased the same property a year earlier for $11 million. The farm was to be sold at a $19 million markup.

The news rocked Paraguay and three years later, in July 2012, the government announced it would not buy the property.

In 2012, two other notable events occurred.

The same month that the government backed away from the purchase of Paso Kurusu, Rodriguez Teixeira announced plans to build an ethanol factory on the ranch that would generate jobs and help indigenous and rural farm communities as well as the small schools that surrounded his property.

![]()

Economic growth and forest reduction

San Pedro, with expanding farms and dwindling forests near the Paraguay-Brazil border, has one of the highest levels of poverty in the country. Yet amid the poverty, the state of San Pedro is abuzz with agro-industrial activity.

In the last 20 years, the region has seen extraordinary growth in soy plantations, from 93,159 acres of soybeans in 2000 to 889,579 acres in 2021, according to data from the official census of the Ministry of Agriculture.

The same is true in Canindeyú, the neighboring state which borders Brazil. The amount of land planted with soybean and other grains increased from 588,358 acres in 2000 to 1,630,895 acres this year.

On a vast stretch of land between the farming states of San Pedro and Canindeyú, Ulises Rodríguez Teixeira forged his empire. He built his fortune in Paraguay on land that was part of the Atlantic Forest, a majestic stand of native trees rich with flora and fauna that is second only to the Amazon in biodiversity in South America. Today, almost nothing remains of this verdant rainforest.

According to the Global Forest Watch satellite forest monitoring system, San Pedro and Canindeyú lost 1,446,705 acres of forest from 2001 to 2021.

A month later, in August 2012, almost 17,300 acres of forest on the Paso Kurusu ranch was destroyed in a fire that firefighters and the Ministry of the Environment confirmed was intentionally set. An investigation of the blaze never resulted in suspects being identified or arrested.

The factory proposal generated excitement in San Pedro, where most of the Paso Kurusu ranch is located. San Pedro has historically been one of the most impoverished states in Paraguay, earning the unenviable ranking of having the second-highest level of extreme poverty in the country. The factory promised to generate jobs for hundreds of families. But years passed and the ethanol factory never materialized in Paso Kurusu.

It was a time when the internet still did not reach a significant number of Paraguayans and few people were aware of the expanding deforestation. But with the passage of time, Ulises Rodriguez Teixeira stopped being the Brazilian known for the “case of Paso Kurusu” and became the Brazilian businessman linked to deforestation.

It is no coincidence that Rodríguez Teixeria’s growth as a landowner parallels deforestation in the states of San Pedro and Canindeyú. As worldwide demand for soybeans has grown, the land has been systematically deforested despite environmental laws that have prohibited logging in the region since 2004.

In San Pedro, Rodriguez Teixeira leases almost all of his Paso Kurusu ranch — some 50,000 acres — to Grupo Pereira, a company which in turn works with a group of farmers to produce soybeans, sunflowers and grains.

Farmland in the San Pedro area leases for about $300 per 2.5 acres per year, depending on market pricing. That pencils out to approximately $6 million per year in revenues for Rodriguez Teixeira solely on the Paso Kurusu ranch.

Rodriguez Teixeria’s business interests extend beyond ranching and agribusiness.

His latest project is the construction of an airport hangar in Luque, 10 miles from Asunción, near the Silvio Pettirossi International Airport, with space for at least a dozen planes and helicopters. According to the project’s Environmental Impact Report, the work covers 65,000 square feet with an initial investment of $725,000.

He is also expanding his business operations to the United States. On August 5, Rodriguez Teixeira and several family members registered a new company — Teixeira International Investment LLC — in Citrus Park, Florida, a community north of Tampa, according to documents filed with the Florida Department of State Division of Corporations.

Those who know Rodriguez Teixeira say he has a hands-on approach to managing his ranches, that he is always attentive to what happens on his land. He prefers to be in his fields than in the office. He directly supervises every detail of his operations.

In the indigenous communities near his properties, Rodriguez Teixeira is seen as a fierce defender of his land. Others who have dealt with him say he is an agile businessman focused on personally solving problems, especially when they involve allegations of environmental violations. Rodriguez Teixeira’s method of dealing with complaints, they say, is quick and effective.

One example stands out. In December 2010, Paraguay’s Congress and approved a law establishing 37,616 acres of Paso Kurusu as a protected wild area with the aim of conserving the forests on the property.

Rodriguez Teixeira appealed to the Supreme Court and in October 2013, the country’s highest court declared the law unconstitutional as Rodriguez Teixeira had requested. But the decision merely ratified what had already been done — the land had been razed before the Supreme Court’s decision was issued.

One of the many interventions carried out by the Ministry of the Environment (MADES) at the Paso Kurusu ranch, owned by the Rodríguez Teixeira family. In this case, the investigation was opened in 2015. Photo: MADES Archive

THE ENVIRONMENTAL COMPLAINTS, THE STRATEGY

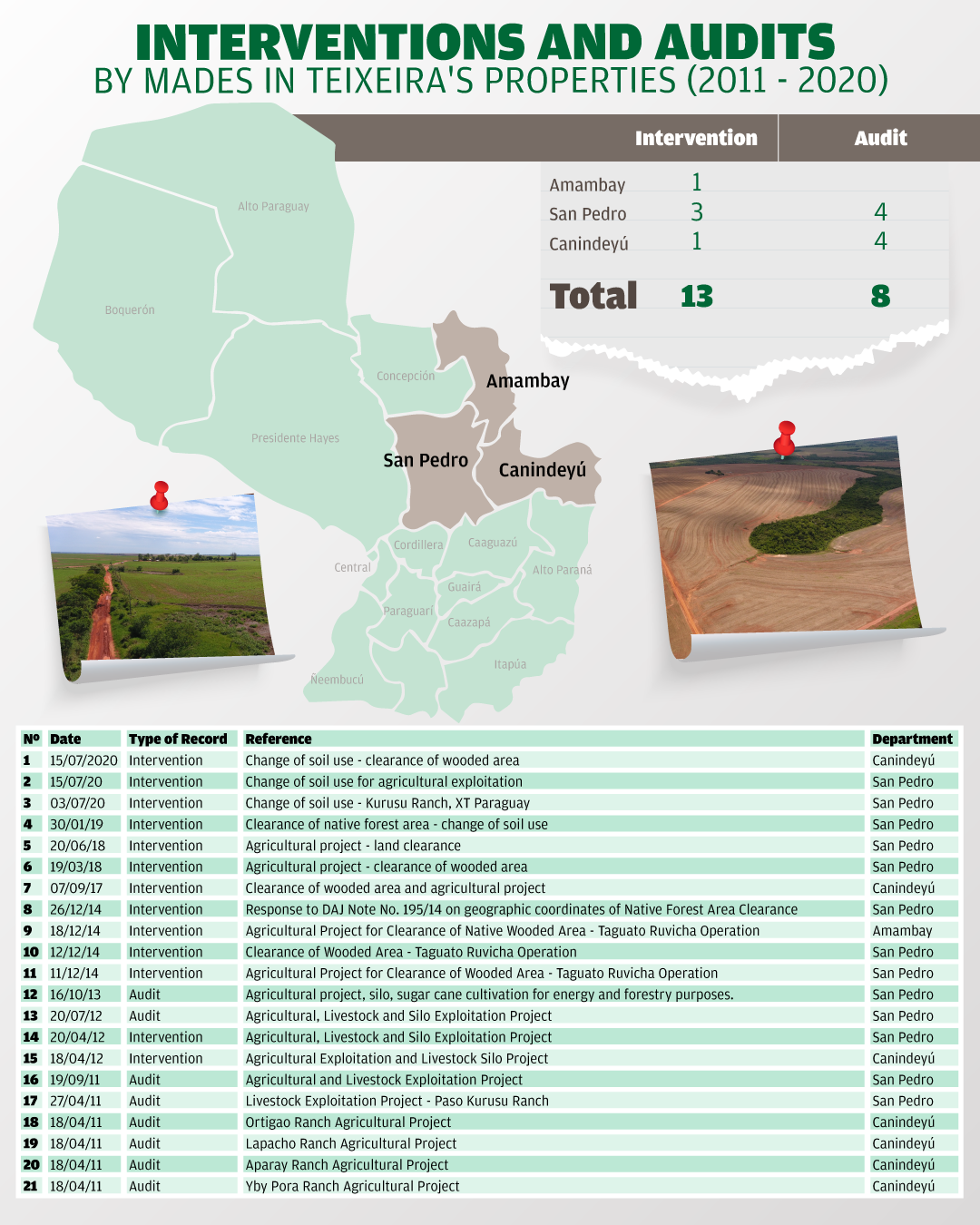

The Paraguayan Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development (MADES) has conducted 21 investigations of environmental complaints against Rodriguez Teixeira – 13 for possible environmental violations and eight inspections. In only eight instances has he paid a fine, according to data from MADES.

The National Forest Institute (INFONA) has carried out five additional interventions from 2018 to 2020 on Rodriguez Teixeira’s ranches. Three cases were due to allegations of an unauthorized change in land use and two cases were related to illegal clearing. All of the cases are under investigation.

The environmental prosecutor’s office has also opened eight investigations — related to clearing, deforestation, land use and other types of environmental violations — into Rodriguez Teixeira’s companies since 2010.

Two are recent — they were opened in July 2020 — and focus on two farms owned by Rodríguez Teixeira on roughly 25,000 acres that extend over two states. Yby Pora ranch, which in the native Guarani language of Paraguay means “good land,” is in the state of San Pedro, while the Santa Teresa ranch is in the state of Canindeyú. Environmental prosecutors from both states have been investigating the deforestation of at least 3,700 acres on the property since July 15, 2020.

In addition to the environmental prosecutor’s office, INFONA is also investigating deforestation on the Rodriguez Teixeira property.

The indigenous people of the Kavaju Paso community allege that XT Paraguay annexed at least 300 acres of the community’s land to Rodriguez Teixeira’s Yby Pora farm. In an interview with Bajo la Lupa, Salvador Esquivel, leader of the community, said the land was fenced off years ago by XT Paraguay, which is now using the property for soy plantations.

A pattern has emerged in the environmental complaints that involve Rodriguez Teixeira’s properties.

First, the land is cleared of trees. If an intervention by authorities occurs — be it MADES or INFONA – Rodriguez Teixeira pays the fine or goes to court, delaying the process. Later, the area that has been stripped of trees is designated as a change in land use. Then it is used for soy plantations despite a law that prohibits the activity. That is what happened at the Paso Kurusu ranch, where despite the deforestation verified by the authorities over the years, its land is used for plantations. The last step is that the land ends up being rented to third parties for farming and Rodriguez Teixeira appears in government registries not as a soy producer but as someone who rents farmland.

The result of this strategy, which has been repeated over and over again, is that the land is converted to agriculture use and is not returned to its natural state of native forests.

The former head of MADES recalls another strategy – Rodriguez Teixeira often doesn’t comply with environmental requirements imposed by the government.

Environmental licenses granted to Rodriguez Teixeira have required him to reforest the areas he destroyed. Environmental licenses are issued to authorize and control activities such as farming and factory installation to ensure they do not have a negative environmental impact or, at the very least, have minimal impact on the environment.

“To renew his licenses, he promised to restore the affected areas with native species, which he never did,” de Barros Barreto said.

Julio Mareco, director of inspection at MADES, said that since he started working at the Ministry of the Environment in 2004, he does not remember another businessman who has been the focus of as many complaints or investigations.

“We have several summaries where the investigations have determined that he violated the environmental laws of this country,” said Mareco. “The environmental offender is one who changes the natural conditions of land. And that has been proven in several of the proceedings opened against the Teixeira companies.”

Paraguayan environmental officials past and present have been challenged by the persistent allegations of environmental violations against Rodriguez Teixeira.

María Cristina Morales, former Minister of the Environment, recalls going “to a ranch in Santa Rosa del Aguaray, San Pedro, (in 2014) where we had received a complaint for deforestation of native forests. We arrived and checked the case. The tractors were still there.”

Morales remembers stopping a staff member who worked on the ranch and asking who was in charge. The staffer told her “the property belonged to Ulises Rodriguez Teixeira.”

One of the entrances to the Aparay ranch owned by the Rodríguez Teixeira family. In the heart of the Atlantic Forest, this property of almost 13,000 acres is used mainly for mechanized agriculture. Photo: Pánfilo Leguizamón

Bajo la Lupa has made repeated attempts since August 2 to contact Rodriguez Teixeira for this report. Representatives of his company, XT Paraguay, said in response to phone requests for an interview that Rodriguez Teixeira’s lawyer, Bader Rafael Torres, is the only person authorized to speak on his behalf.

For almost a month, at an interval of every two to three days, Bajo la Lupa has contacted Torres about this report, either by phone or by WhatsApp messages.

At Consultora Alta Vista SA, where Torres is listed as one of the partners, the law firm’s personnel said Rodriguez Teixeira would contact Bajo la Lupa when he was available for an interview. To date, he has not contacted this reporter.

In environmental circles, “Rodriguez Teixeira is an emblematic name for us,” said Oscar Rodas, director of World Wildlife Federation (WWF)-Paraguay. “For 21 years we have been denouncing deforestation in various properties of this businessman.”

Rodas said the deforestation of areas such as Paso Kurusu significantly alters the ecosystem of the region. But despite the documentation of environmental damage, the tree-harvesting machinery at Rodriguez Teixeira’s properties has never stopped.

FERTILE TERRITORY

In Paraguay, there are only 12 prosecutors who specialize in environmental crimes. In places such as Canindeyú or San Pedro, only two agents respond to complaints. In addition, they sometimes have to deal with other complaints not related to environmental crimes.

Néstor Narváez is the only prosecutor in charge of handling all the environmental cases in the state of San Pedro, which is practically the size of Israel. It is also a region that has constant conflicts and complaints of deforestation and other environmental crimes.

But that’s not all. Narváez has to handle Civil, Childhood and Adolescence and Economic Crimes in the city of Santa Rosa, 50 miles from the state capital. “I have at least one or two oral trials a week, preliminary hearings three or four a day in Santa Rosa. We try to respond to all the complaints that come to us,” Narváez said, “the most urgent ones at least.”

There are only 11 prosecutors who carry out investigations on deforestation and other environmental crimes in the 10 states that house the Atlantic Forest.

Meanwhile, at MADES, 15 inspectors must respond to all kinds of complaints for environmental crimes, not only those related to clearing or deforestation at the federal level.

The Department of Forests and Environmental Affairs (DEBOA) of the National Police is located in the city of Capiatá, 150 miles from the Atlantic Forest. The office is equipped with a van and eight agents to cover the complaints it receives from all over the country.

Compounding the problem, 2021 is the second consecutive year that Paraguay’s Congress has cut the $4.4 million annual budget of MADES. Officials at MADES officials say there are no funds to hire additional personnel.

There is also a lack of judges specialized in environmental law, which often means that the final judicial determinations are not based on environmental issues.

In Paraguay the environmental regulations seem strict compared to neighboring countries. The problem is in the application of the sanctions. In other words, impunity.

THE BEGINNING OF THE END OF THE FOREST

Oscar Rodas, director of WWF-Paraguay, believes a great opportunity to create a large sustainable forestry project in Paraguay has been lost.

The Eastern region of Paraguay once had almost 14 million acres of forest, an area equal to that of Croatia, according to a report by the National University of Asunción. Today, fewer than 5 million acres remain.

A lone tree stands in a soybean field in what was once the Atlantic Forest. In the last 10 years, 85 percent of the forest has been logged. Photo: Alamy

The loss of biodiversity and a sustained forest system is irreplaceable.

“It could be producing around $20 million a year, just with the value of the wood. With sustained growth, with a system to avoid deforestation, the productive forest is much more valuable, ” said Rodas. “We have lost too much. It is time to find ways to avoid continuing to destroy, to aim for a system that can be sustainable.”

WWF has grown weary of reporting on the clearing of land in Paraguay, much of it owned by Rodríguez Teixeira.

Julio Mareco, director of inspection of MADES, says that after 17 years of fruitless attempts to stop deforestation, he is growing weary, too. He is tired of carrying out legal interventions on Rodriguez Teixeira’s land and seeing that those efforts have not paid off in the restoration of the Atlantic Forest.

As more and more trees disappear with each passing year, Mareco and others who have worked to protect the forest are haunted by a disquieting thought. If the deforestation continues unchecked, Paraguay will end up losing its forest and the Eastern region will be completely bare.

Paso Kurusu

CONTINUE

Sea of deforestation

CONTINUE

David vs. Goliath

CONTINUE